Complexity & Control: Is Friction the Enemy...or is it Friend?

Inspired by one of my favorite podcasts: Machine Learning Street Talk (MLST)

In the most recent episode of

, Professor Christopher Summerfield from Oxford University talks about his new book: These Strange New Minds: How AI Learned to Talk and What It MeansFor those of you who know me, you’ll have likely heard me quote Dr. John Gall from his book The Systems Bible in which John says:

A complex system that works is invariably found to have evolved from a simple system that worked. A complex system designed from scratch never works and cannot be patched up to make it work. You have to start over with a working simple system“

As I dig deeper into the AI world upon us, I find this quote and these concepts to be paramount. I recommend you listen to the podcast as I’ve listened to this episode twice. If you don’t have the time or are not that as much of a geek as me, here are my thoughts on a small part of this intellectual feast on AI, psychology and society.

Let’s start with a simple premise: if you build a system capable of interacting in complex ways, you’ve just built something more powerful—and more dangerous—than you may realize. It doesn’t matter if it’s a financial trading algorithm, a legal automation engine, or a swarm of conversational AIs. Once complexity reaches a certain threshold, it begins to behave in nonlinear, unpredictable, and often chaotic ways. This isn’t speculative. This is observable, recurring, and deeply unsettling.

Here's where Silicon Valley—and increasingly, our entire civilization—gets it fundamentally wrong. We worship "frictionless experience" like it's salvation itself, engineering out every bump, delay, and moment of resistance as if they were design flaws rather than essential features. But examine any genuine transformation, whether in human development or complex systems, and you'll discover something unsettling: friction isn't the enemy of progress. It's the guardian of sustainability.

As a friend Riwa said recently, “Innovation as the reduction of friction misses the fact that we’re here to have a journey. If you strip the journey out, you’re robbing people of what creates character.”

Second Order Cybernetics

In 1999, I had the privilege to meet Dr. Heinz von Forester to medically escort him to Vienna to receive ‘keys to the city’ by the mayor for his discovery of second order cybernetics. At the time, I’d never heard of the gentle old living in Half Moon Bay, California.

Heinz von Foerster's insights into second-order cybernetics reveal a crucial distinction we've forgotten in our rush toward automation: the difference between systems that simply respond to feedback and systems that can observe themselves responding. First-order cybernetics asks "How do systems maintain stability through feedback?" Second-order cybernetics asks the deeper question: "Who is observing the system, and how does that observer shape what they see?"

This distinction becomes critical when we examine human progress. We aren't just goal-seeking machines optimizing for outcomes—we're self-aware systems capable of questioning our own goals, adjusting our definitions of success, and choosing stability over immediate optimization when wisdom demands it. The friction in human decision-making isn't inefficiency; it's the space where second-order observation occurs—where we pause to ask not just "How do we achieve this goal?" but "Should this be our goal at all?"

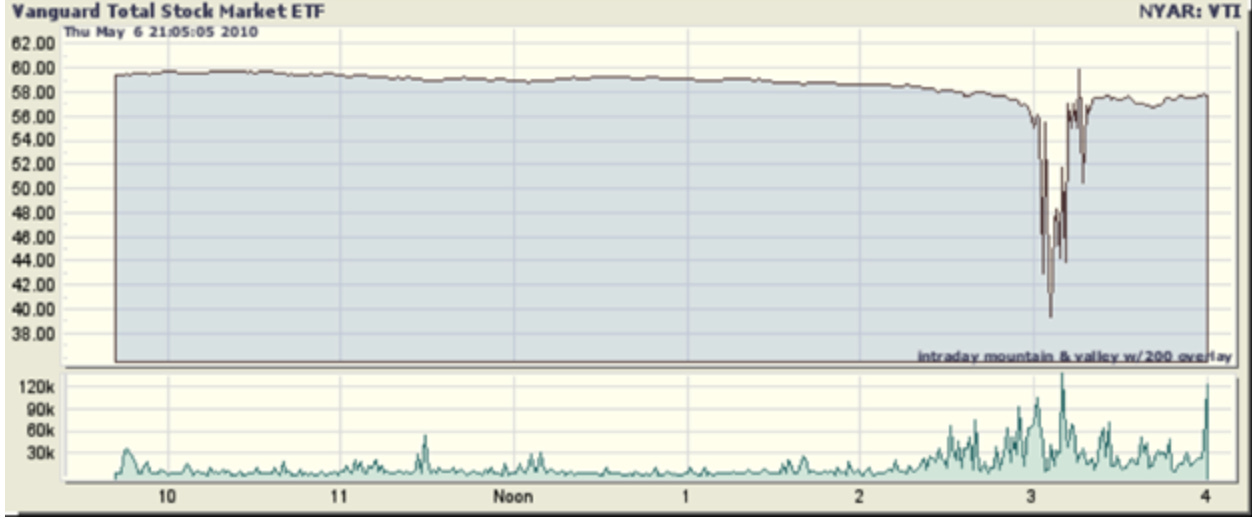

Consider the Flash Crash that happened on May 6, 2010, when the U.S. stock market dropped nearly 1,000 points in minutes before mysteriously recovering. This wasn't market sentiment gone wrong—it was complex systems operating exactly as designed, just without the cultural circuit breakers that normally prevent catastrophic feedback loops. Dozens more flash crashes have followed, each one a stark reminder that when you strip away the natural friction of human decision-making, you don't get elegant efficiency. You get chaos. The problem isn’t just that these systems are fast; it’s that they operate under no evolved norms. Unlike human societies, which have spent millennia developing cultural guardrails—ethical instincts, social contracts, even the inefficiencies of paperwork—these systems don’t “know” when to stop. They just go.

The 2010 flash crash revealed something profound about the architecture of stability: human institutions aren't slow because they're poorly designed. They're slow because slowness serves a function. Laws, bureaucratic processes, even the inefficiencies of paperwork—these aren't bugs to be eliminated. They're features that force consideration, create breathing room for second thoughts, and impose costs that naturally limit abuse.

And here lies the crux: humanity has built its institutions around natural frictions. Laws, norms, bureaucratic delays—these are often seen as annoyances, but they function like circuit breakers. They slow us down just enough to prevent the social equivalent of a flash crash. Most people don’t know how to abuse the legal system, not because it’s impossible, but because the friction—cost, expertise, time—is high. Remove those, and the system can collapse under the weight of its own accessibility. This is what AI threatens to do: make everything too easy, too fast, too illegible.

Legibility matters. In wartime, there is the concept of the “fog of war”—a loss of clarity that impairs decision-making. In AI, it may be better called the “fog of agency”: a loss of control due to the scale, speed, and abstraction of autonomous systems acting on our behalf, beyond our comprehension. When millions of agents are empowered to act without the cultural “governors”, the inherited wisdom, ethical instincts, and social contracts that shape human judgment. We’re not just unleashing tools, we’re releasing new actors into a drama that no one is directing.

This isn't speculative concern—it's observable reality. Financial algorithms trigger market volatility. Content recommendation systems reshape political discourse. Legal automation tools threaten to flood courts with frivolous cases. Each represents the same pattern: remove human friction, achieve temporary efficiency gains, then discover that the friction was serving essential functions we didn't understand until it was gone.

Some argue we should design constraints into these systems. But to do so, we’d need to accept limits—on efficiency, on optimization, on profit. That’s a hard sell in a world drunk on scale. Yet without those constraints, we’re building systems with more degrees of freedom than we’ve ever seen—more than language, more than markets, perhaps more than states.

In short, we’re building the conditions for systemic crashes—social, economic, informational—not out of malice, but out of naivety. We’ve mistaken friction for failure, when in fact, it’s one of our greatest forms of protection.

And so the question remains: in a world where AI can act faster, broader, and more subtly than any individual or institution, who—or what—applies the brakes? Because if no one does, the next flash crash may not just be financial. It may be civilizational.

Just sayin’.

I enjoyed the Euphoria exhibit in Paris made up mostly of balloons and bubbles. It was deliciously analog.