The Architecture of Health: Reimagining Medical Language Through Leverage Points

Could our words hold the key to systems change in healthcare?

I often think of language as a form of architecture—words are the walls and hallways we move through in our minds. Our vocabulary, especially in the realm of medicine, can either confine us in tight, mystifying corridors or open us up to spacious rooms of clarity and empowerment. Yet, as the legendary systems analyst Donella Meadows once wrote, any system—be it a city, a corporation, or an entire healthcare paradigm—contains “leverage points,” places where small shifts can produce big changes. If language is the framework of our mental architecture, then altering our medical vocabulary could be a profound act of remodeling at precisely the right leverage points.

I. Language as a House We Live In

The idea that “the words we speak become the house we live in” as observed by the 14th century Persian poet Hafiz is an enduring testament to the power of language.

In healthcare, we see linguistic “floor plans” built on archaic Greek or Latin terminology, terms like “diabetes” (Greek for “siphon”), which merely describes excessive urination. This word offers no hint of the root causes nor a path for prevention. What if we instead called Type 2 diabetes “processed food overconsumption syndrome”? Suddenly, the architecture shifts. Prevention and responsibility become visible in the very name.

Language is a massively flawed, totally imprecise messed up collection of agreements made up by a bunch of people in the past. No deity handed down our current words, nor were they written into the universe.

We must be careful of the stories we tell ourselves, because those stories become how we see the world.

Austrian philosopher Wittgenstein argued that the world we see is defined and given meaning by the words we choose. However, communicating thoughts through the filter of language runs into two issues:

We use language imprecisely

We try to use language to describe something that language is completely incapable of describing

According to German philosopher Heidegger, language and formal logic are a prison that we are trying to break out of. Language requires a structure predicated on a subject acting on an object.

Even within these constraints, language has an outsized influence on how we see ourselves or treat other people.

Shifting language shifts perspective, moves us out of old mental maps to make space for different questions that help break us out of the prison of our limited worldviews.

In healthcare, focusing on clear root causes changes how people think about and address disease. This could include highlighting cellular pathology - for example, Parkinson’s Disease becomes “dopamine-depletion movement disorder” - all the way to social determinants of health, where “addiction” or “substance abuse disorder” is relabeled “loneliness disorder”.

Currently, most healthcare costs and patient suffering are driven by a constellation of interrelated metabolic syndromes such as atherosclerotic heart disease, stroke, some cancers, diabetes and neurodegenerative disorders. They are often interpreted by patients as being irreversible, condemned to a lifetime of medication and deterioration. But what if we pointed to their root cause - our modern, fast-paced lifestyles and environment with disrupted nutrition, exercise, stress and sleep - by referring to them as “lifestyle-related preventable disease” instead? Now it opens up the possibility of a better conversation, away from blame and shame to one of agency for the patient, focused on improving both health span and lifespan. It also allows the physician to embody the teacher and guide role inherent in their title “doctor” (from the Latin root “docere”, meaning “to teach”).

This is not just a linguistic curiosity; it’s a reordering of the entire conceptual space in which healthcare policies are planned and understood.

II. Systems Analysis 101: Finding the Leverage Points

To understand why renaming diseases might have such a dramatic impact, it helps to step briefly into the world of systems analysis—a field that looks at how complex systems (ecosystems, corporations, governments) behave.

SYSTEM

The word “system” derives from the Greek “synhistanai” which means “to place together.”

A system is a set of interconnected elements which form a whole and show properties which are properties of the whole rather than of the individual elements. This definition is valid for a cell, an organism, a society, or a galaxy.

SYSTEMS THINKING

Systems thinking means thinking in terms of relationships, patterns, connectedness and context.

It allows us to understand how things work, identify root problem causes, see new opportunities, make better decisions and adapt to changing circumstances.

When we think this way, we quickly realize that none of our major problems can be addressed and solved in isolation.

LEVERAGE POINTS

“When we try to pick out anything by itself, we find it hitched to everything else in the Universe.” John Muir

While this sentiment conveys the idea that “everything is connected”, it can also be overwhelming or paralyzing and get in the way of action. However, a deeper look reveals that everything is not equally, completely or randomly connected - and this allows us to identify the points in the system that are the most impactful to instantiate change.

Leverage points are these points of power in the system.

Donella Meadows famously outlined twelve leverage points—places where a small change in one component can send transformative ripples through the entire system. Although there are many nuances to these leverage points, let’s look at why language—and the mindsets behind it—occupy some of the highest rungs on Meadows’s hierarchy.

12. Parameters (Taxes, Standards, etc.) – Adjusting parameters in healthcare, such as the cost of services or the recommended daily allowance of certain nutrients, often draws the most debate. But these changes, while politically charged, rarely address root causes or transform outcomes in a systemic way.

11. Buffers and Stocks – We can alter the size of our “health buffers,” like strategic reserves of essential medicines. Helpful, but again, it rarely remakes the entire system.

10. Structure of Material Flows – Think of hospital supply chains or emergency-room layouts. Changing these can improve efficiency, yet it still might not revolutionize our understanding of disease.

9. Delays – Healthcare is riddled with delays, from the time it takes a new drug to move through the FDA approval process to the onset of a chronic disease from poor diet. Reducing detrimental time lags can help, but it’s still not the prime leverage point for reshaping how we think about health.

8. Strength of Negative Feedback Loops – These loops keep a system in balance, like a thermostat regulates temperature. In medicine, negative feedback loops might mean expanding preventive care or “check-ups” that stabilize health before it collapses. Strengthening such loops is key, but we can still go deeper.

7. Driving Positive Feedback Loops – These are self-reinforcing spirals, such as “success to the successful.” In healthcare, a positive loop might mean that people with better information and resources stay healthier, while those without spiral downward. Reducing these inequities is crucial, but not yet the heart of the matter.

6. Information Flows – When patients have transparent data about their conditions, they can make better decisions. Placing an electric meter in the front hallway slashes power usage by reminding people how much they consume. In the same vein, straightforward medical terminology that illuminates environmental or behavioral causes can prompt healthier decisions.

5. Rules of the System – Rules define the boundaries of what’s allowed. In healthcare, these might be policies on reimbursement, insurance coverage, or licensure. Changing the rule that transforms a “doctor” into a mere “provider” devalues the professional–patient relationship, creating distance rather than trust.

4. Power to Add, Change, or Self-Organize – Living systems—and some human institutions—can evolve, generating new structures and solutions. Healthcare can learn from nature’s ability to reorganize around threats, whether that’s a new virus or a chronic illness epidemic.

3. Goals of the System – A system’s overarching goal drives all subordinate goals. When the goal is simply “maximize profits,” we see certain biases in research priorities and treatments offered. Shifting that goal to “maximize quality of life” or “foster well-being” changes resource allocation throughout the system.

2. Mindset or Paradigm Out of Which the System Arises – A society’s deepest beliefs—about growth, autonomy, responsibility—shape how it deals with health. Do we consider individuals passive recipients of disease, or active participants in their own well-being? Do we treat the environment as peripheral to health, or see it as central?

1. Power to Transcend Paradigms – The highest leverage point is to step outside one’s current worldview entirely. This means recognizing that no single mental model—whether of health, economics, or politics—captures the full complexity of reality. From that vantage, we can choose or create paradigms that better serve our global needs.

“So how do you change paradigms? In a nutshell, you keep pointing at the anomalies and failures in the old paradigm, you keep coming yourself, and loudly and with assurance from the new one, you insert people with the new paradigm in places of public visibility and power. You don’t waste time with reactionaries; rather you work with active change agents and with the vast middle ground of people who are open-minded. “ Donella Meadows

III. Medical Language at the Highest Leverage Points

Now, how does medical language fit in? Look no further than the top three leverage points Meadows described:

3. Goals of the System

Our healthcare system often prioritizes treating illness rather than preventing it. This underscores a deeper social goal: to address problems after the fact, rather than anticipating and mitigating them. If we rename conditions to highlight personal habits and environmental influences, the system’s natural pivot might be toward prevention. Funding streams, educational curricula, and public health campaigns would then reinforce staying healthy, not merely responding to sickness.

2. Mindset or Paradigm

Language can be a gateway to shifting paradigms. If we persistently name diseases in a way that reveals root causes—diet, pollution, stress—we shift our cultural mindset from “diseases just happen” to “we play an active role in creating or preventing them.” Ancient Latin labels obscure agency; plain-spoken cause-and-effect words illuminate it.

1. Transcending Paradigms

Ultimately, new vocabulary can help us question cherished assumptions—like the belief that every condition can be “fixed” with a pill, or that economic growth automatically solves public health challenges. As Jay Forrester discovered, growth can worsen environmental conditions, leading to more health problems, not fewer. To transcend these habits of thought, we need to be bold about naming the fundamental issues: corporate pollution in our bodies, the myth of infinite consumption, and the systemic undervaluing of preventative care.

IV. Corporate Influence and “Backward Intuition”

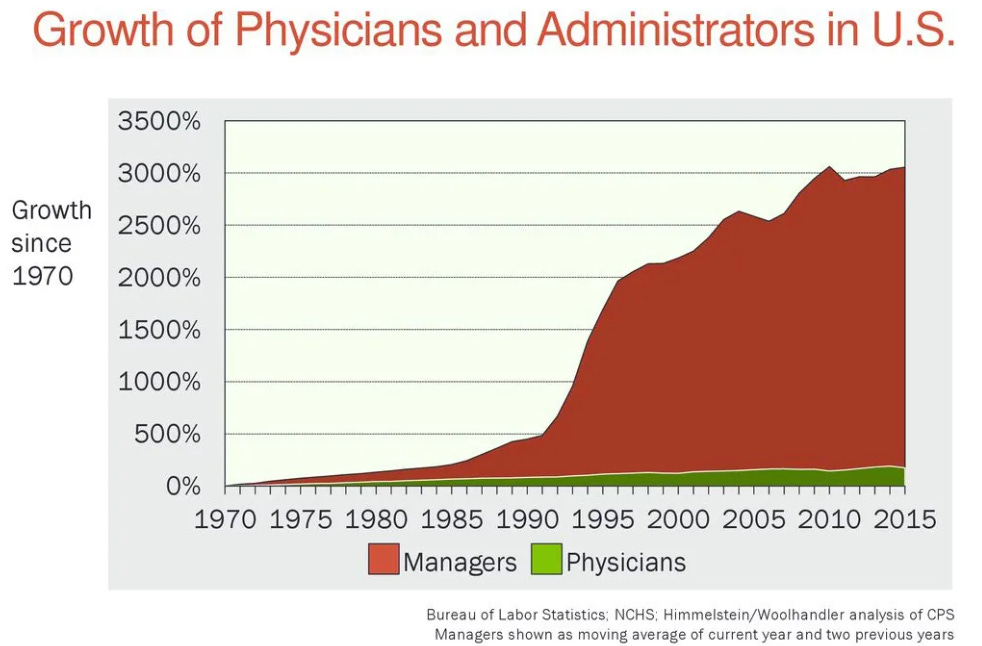

Donella Meadows recounts how her mentor, Jay Forrester, would identify a leverage point—say, a company’s inventory policy—and then see that people intuitively recognized that same point…only to push it in the wrong direction. This “backward intuition” is clear in how healthcare institutions handle terminology. We’ve replaced “doctor” with “provider,” “payment” with “reimbursement,” layering distance between human beings and their well-being. (pro-tip - stop using the word ‘provider’ to describe a person in healthcare, say clinician - this honors the fact that a human was trained in the healing arts. I remind my friends that an uber driver is also a ‘provider’ a provider of a ride. The use of the word “provider” dehumanizes, de-identifys and concentrates power by the people who use this language - mostly healthcare administrators.

In a similar way, policymakers often fixate on short-term, parameter-level solutions (like adjusting insurance codes) but fail to question the entire linguistic scaffolding that frames healthcare as a commoditized service. By creating new language structures that reveal accountability and encourage prevention, we might unlock the correct direction of push.

V. Renovating the House of Medicine

Just as we’d tear down load-bearing walls and rebuild a poorly laid-out home, our medical language calls for a remodel. Converting archaic terms into cause-oriented labels is like installing bigger windows in a dark room—it floods the space with clarity. However, the challenge remains: systems resist change at their highest leverage points. Paradigm shifts and shifts in core goals can face fierce opposition from vested interests.

Still, the potential rewards are enormous. When environmental factors are accounted for in the very names of medical conditions—when we label health professionals in ways that highlight relationships, not transactions—we move closer to Donella Meadows’s vision of a healthy, self-regulating system that thrives on feedback loops and focuses on real causes rather than superficial fixes.

VI. Building a House That Heals

We have the power, as architects of language, to build a new “house of health,” one that is stable enough to foster well-being yet flexible enough to evolve with the changing needs of humanity. Donella Meadows’s list of leverage points reminds us that the highest-affected changes often arise when we question our deepest assumptions — about growth, about what health really means, and about the words we use to describe our bodies and our environment.

So let us take a lesson from systems analysis and from Hafiz. The words we live by are not mere labels; they are cornerstones of our collective paradigm. By renaming diseases to reflect their root causes, by resisting “backward intuition” that dilutes the doctor–patient bond, and by transcending the status quo paradigm, we can truly renovate the house we inhabit. In doing so, we spark the kind of paradigm shift that has the power to redefine our reality, making prevention visible, personal agency tangible, and a healthier future entirely possible.

As a start, let’s avoid the terms:

Provider, use clinician

Reimbursement, use payment

Consumer, use customer or patient. Consumers want to go to the Apple Store, not the Urgent Care Store. That said, there is an uptick in people spending their money (not insurance money) on tools for insights and access to services that the healthcare system has failed to provide

Avoid using acronyms

Healthcare System, use Sickcare System - and it’s charitable to even call it a system.

I invite you to share the words you would change. Please add them in the comments and thanks your for getting to the end.

Love this and will nicely dovetail into my wellness center idea. Working on convincing the hospital to join me in this endeavor. !