I know I’m right. You’re wrong. Why can’t everyone see what I see? Why are people arguing over things we already know to be true? What is wrong with them?

As my mother—a sharp, no-nonsense psychotherapist—likes to say, “You can be right, or you can be in a relationship.” Being right feels good, but what if there’s no absolute “right” to begin with?

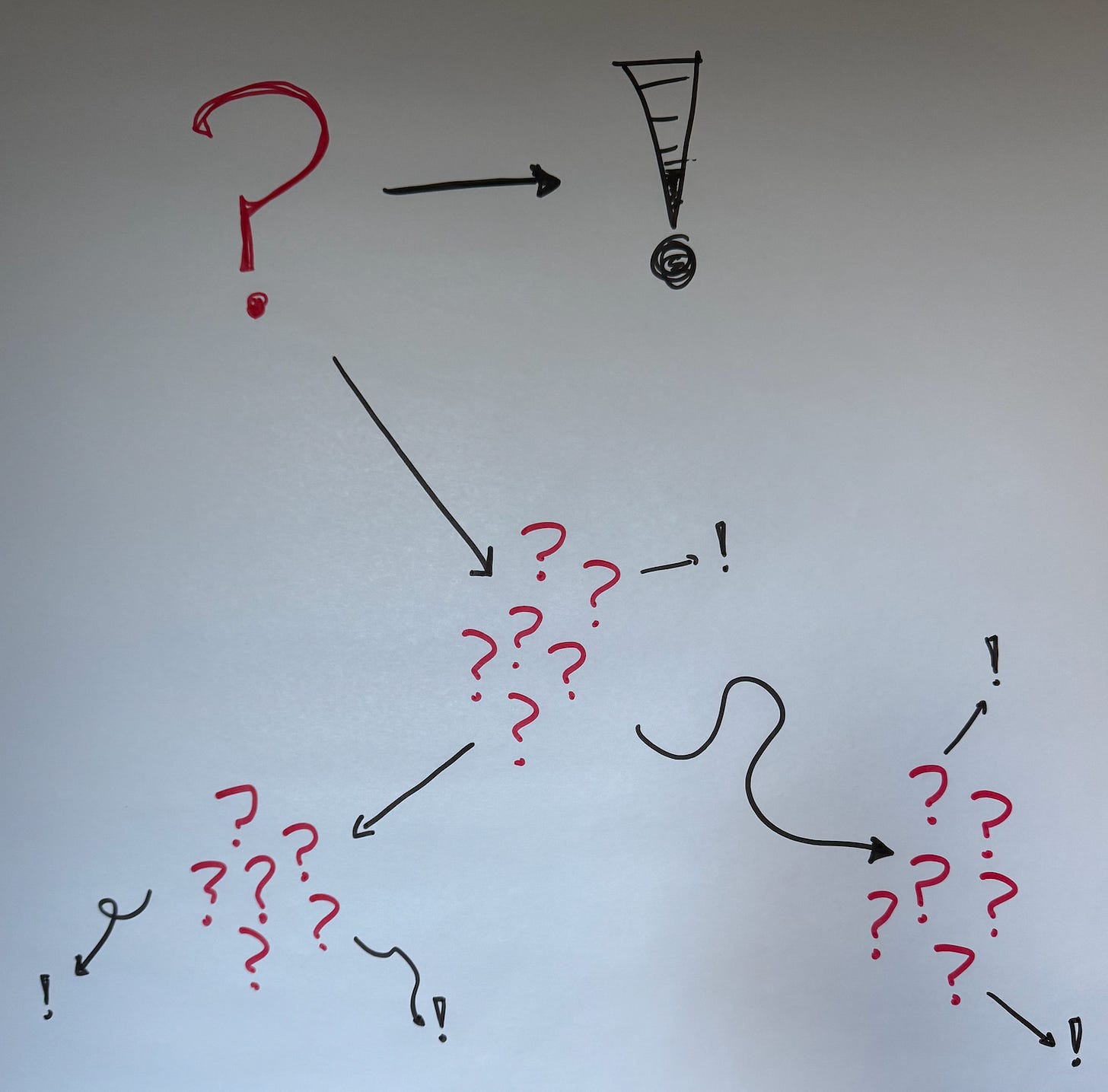

For centuries, we've built our understanding of the world through questions: Why? How? What if? We seek answers, and from them, we construct intricate systems of knowledge. But these answers—whether discovered or declared—are never absolute truths. They are approximations, filtered through the messy, subjective lens of human perception. Reality isn’t just what we know. It’s what we think we know.

Ernest Becker’s Denial of Death explores the idea that human belief systems are not absolute truths but rather hypotheses—mental constructs we use to manage the terror of our own mortality. The more we tether our identity to these beliefs, the more fragile we become, as any challenge to them feels like a direct attack on the self. When ego and belief are too tightly intertwined, the prospect of being wrong becomes unbearable, a kind of symbolic death that stifles growth, curiosity, and adaptation. But if we loosen that grip—if we see beliefs as flexible, provisional, and subject to change—then curiosity flourishes, and we remain intellectually and emotionally alive. In contrast, those who refuse to question their convictions may find themselves trapped in a rigid, defensive existence, long before their biological death ever arrives. State simply, being wrong is a symbolic death which may be more painful because it happens when we’re alive.

The question-answer paradigm serves as a scaffolding for our comprehension, but, like any framework, it has inherent limitations. When we pose a question, we already constrain the possible answers by the very framing of our inquiry. The framework itself becomes a lens that both enables and restricts our vision.

A deep tension between pride and humility characterizes our relationship with truth. Pride whispers or shouts, that our answers are complete, that our understanding is sufficient. It insidiously calcifies our perspectives and leads us to mistake our partial maps for the full territory. The proud mind proclaims, "I know," and “I’m right,” and in that proclamation closes itself to deeper understanding. Throughout history, intellectual pride has been the enemy of discovery—a force that resisted Copernicus's helio-centrism, dismissed continental drift, and mocked the notion of washing hands before surgery.

Consider scientific understanding. What we call scientific "truth" today exists as a refined probability—a model that best explains our observations until a better one emerges. The pessimistic meta-induction theory reveals this provisional nature of scientific knowledge: history shows that we have eventually proven our most successful scientific theories false or incomplete. If our predecessors were consistently wrong about what they considered established truths, we must confront the humbling possibility that our current scientific "truths" await a similar fate. People considered Newton's laws of motion absolute truths until Einstein revealed their limitations on extreme scales. What was "true" became merely "accurate enough for most purposes." Science progresses not by discovering ultimate truths but by developing increasingly precise approximations. Its greatest advances have come not from pride in established knowledge but from the humility to question it.

Humility acknowledges the provisional nature of our understanding. It recognizes that every answer, no matter how elegant or comprehensive, remains incomplete. The humble mind approaches knowledge not as a possession to defend but as a landscape to explore. It understands that our answers reflect degrees of accuracy rather than absolute truth, and it remains open to refinement and revision.

Language itself further complicates our pursuit of truth. The study of semiotics reveals that words are crude, unstable instruments—mere containers for ideas that often fail to transmit the true nature of the 'idea' they attempt to convey. The signifier never perfectly captures the signified. What we call "chair" bears only a tenuous, arbitrary relationship to the actual object, and even less to the abstract concept of "chairness." The words we use to frame questions and articulate answers carry their own limitations, ambiguities, and cultural baggage. They shift in meaning across time, context, and individual interpretation, creating a perpetual game of broken telephone between minds. How can we access pure truth when our very tools for describing it are so fundamentally imperfect? The map is not the territory; the word is not the thing itself. Humility recognizes these limitations of our symbolic systems; pride ignores them and mistakes the vessel for its contents.

Language itself further complicates our pursuit of truth. The study of semiotics reveals that words are crude, unstable instruments—mere containers for ideas that often fail to transmit the true nature of the 'idea' they attempt to convey. The signifier never perfectly captures the signified. What we call "chair" bears only a tenuous, arbitrary relationship to the actual object, and even less to the abstract concept of "chairness." As Jaques Derrida argued, meaning is never fixed but endlessly deferred, caught in a web of differences where each word gains significance only in relation to others. There is no final, stable reference point—only a shifting play of signification that destabilizes our confidence in language as a transparent medium of truth. The words we use to frame questions and articulate answers carry their own limitations, ambiguities, and cultural baggage. They shift in meaning across time, context, and individual interpretation, creating a perpetual game of broken telephone between minds. How can we access pure truth when our very tools for describing it are so fundamentally imperfect? The map is not the territory; the word is not the thing itself. Humility recognizes these limitations of our symbolic systems; pride ignores them and mistakes the vessel for its contents.

Perhaps what we call "truth" is better understood as varying degrees of accuracy—models that correspond with reality closely enough to be useful within specific contexts. A weather forecast may be accurate enough to help us decide whether to carry an umbrella, without being absolutely "true" in predicting the exact rainfall pattern. The humble thinker values this utility without mistaking it for completeness.

This perspective doesn't consign us to nihilism or suggest that all claims are equally valid. Some maps correspond more closely to the territory than others. Some answers align more consistently with observable phenomena. The value lies not in attaining absolute truth, but in recognizing the provisional nature of our knowledge and remaining open to refinement.

In embracing this understanding, we might approach knowledge with greater humility and curiosity. If nothing is absolutely true, but many things are relatively accurate, we can hold our beliefs more lightly while still moving forward with practical wisdom. We can value the utility of an answer without mistaking it for ultimate reality. Pride clings to certainty; humility thrives in possibility.

The paradox within the concept that The Truth Is Not True invites us not to abandon the pursuit of understanding, but to pursue it with an awareness of its inherent limitations. In a world without absolute truths, we find freedom—to question, to explore, to refine our understanding in an endless journey of discovery. The absence of final answers doesn't diminish the value of asking better questions. It merely requires humility to recognize that today's answer may become tomorrow's question, and the pride we take in our knowledge should never exceed our willingness to revise it.

Perhaps in this recognition lies a profound insight: curiosity itself is happiness. When we suspend our attachment to fixed beliefs and embrace curiosity, we enter a flow state that liberates us from the anchors of the past. The curious mind dwells not in static being but in dynamic becoming. It exists at the exhilarating interface between the present and the future—that fertile edge where what is known touches what might be discovered. This is the ancient tension between being and becoming that philosophers have wrestled with since Parmenides and Heraclitus: are we defined by our stable essence or by our constant transformation?

The truth may not be true, but in the space created by this uncertainty, we find not despair but joy—the joy of perpetual discovery, of minds unbound by the illusion of completion. In embracing the provisional nature of knowledge, we don't abandon truth; we dance with it, participating in its continual unfolding. And in this dance of becoming rather than merely being, we find a deeper fulfillment than any static "truth" could provide.

The state of being curious is how we become ourselves; seeking accuracy, we flow in and around the transcendent state of happiness.

Ask not for the fastest answer, but for the question that makes you pause. Ask not for certainty, but for clarity. Ask not just what you believe, but why you believe it.

In a world desperate for the quick fix, the life hack, the influencer-backed miracle cure, the real rebellion isn’t in knowing—it’s in wondering. It’s in stepping back from the dopamine rush of certainty and choosing instead to wade into the exhilarating, sometimes terrifying waters of the unknown.

The Instagram guru may promise you the "one trick" to wellness, the "three steps" to longevity, the "five foods" that will change your life. But what if the real secret—the one that actually matters—isn’t an answer at all? What if it’s a question? A slow-burning, uncomfortable, paradigm-shifting question that doesn’t promise relief but instead demands engagement?

What if the secret to being "right" isn’t having the answer, but being willing to ask again, and again, and again?

The difference between those who merely consume knowledge and those who shape it is simple: the first group stops at the answer. The second group never stops questioning.

We don’t need more gurus. We don’t need more shortcuts. We need more people willing to do the harder thing—the thing that makes people uneasy in dinner conversations and unsettles boardrooms and rattles the status quo. We need people willing to ask:

What if I’m wrong?

And then, rather than fearing that possibility, rather than clinging to being “right,” they lean into the question.

Because the truth—the real truth—is not a static thing to possess. It is a living, shifting, evolving process. And the best thing you can do for yourself, for the world, for knowledge itself, is to stop chasing the answer and start loving the question.

So, ask. And keep asking.

The right question is worth more than a thousand wrong answers.

This piece is a masterpiece of thought and language - a profound meditation on the nature of truth that inspires both wonder and introspection. Each sentence is a carefully crafted invitation to explore the beautiful ambiguity of our beliefs, urging us to cherish the art of questioning over the comfort of certainty.

Thank you, Jordan, for challenging us to embrace the unknown and find poetry in every inquiry.